Oct 3, 2018 12:00:00 AM

by Erika Sanzi

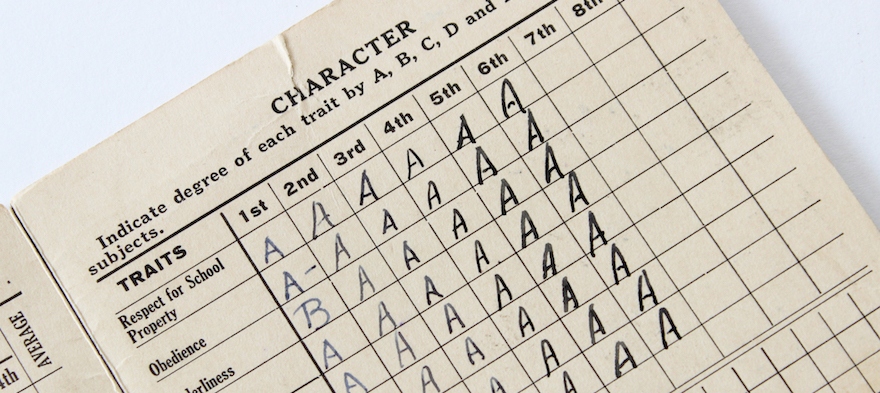

Conscientious parents are constantly getting feedback about the academic performance of their children, almost all of it from teachers. We see worksheets and papers marked up on a daily or weekly basis; we receive report cards every quarter; and of course there’s the annual (or, if we’re lucky, semiannual) parent-teacher conference. If the message from most of these data points is, “Your kid is doing fine!” then it’s going to be tough for a single “score report” from a distant state test administered months earlier to convince us otherwise.And he adds that “nobody wants to tell parents to grab a pitchfork and march down to their school demanding an explanation for the lofty-yet-false grades their kids have gotten for years on end. Maybe they should.” Parents wielding pitchforks are not out of the ordinary in affluent communities when it comes to the demand for better and higher grades so the likelihood that they’d change course and start banging the drum for fewer “lofty yet false” grades is pretty remote. But it needs to happen. I’ve got my pitchfork ready.

Erika Sanzi is a mother of three sons and taught in public schools in Massachusetts, California and Rhode Island. She has served on her local school board in Cumberland, Rhode Island, advocated for fair school funding at the state level, and worked on campaigns of candidates she considers to be champions for kids and true supporters of great schools. She is currently a Fordham senior visiting fellow.

Few issues in education spark more tension and debate than standardized testing. Are they a tool for equity or a burden on students? A necessary check on school systems or a flawed measure of...

Charter schools are public schools with a purpose. Operating independently from traditional school districts, they're tuition-free, open to all students, and publicly funded—but with more flexibility...

Despite the benefits of a diverse teaching force, prospective teachers of color fall out of our leaky preparation pipeline at every stage: preparation, hiring, induction, and retention. Here’s what...

Ed Post is the flagship website platform of brightbeam, a 501(c3) network of education activists and influencers demanding a better education and a brighter future for every child.

© 2020-2025 brightbeam. All rights reserved.

Leave a Comment