Jan 11, 2021 12:00:00 AM

by Debbie Meyer

When I give presentations about dyslexia, I often illustrate how neurodiversity works by showing a chessboard. Some people can easily see all the patterns of moves on a chessboard and can play out a game ten moves or more at a time in their head. Other people struggle to memorize the movement patterns of each piece.

Over a recent weekend, I binge-watched “The Queen’s Gambit” and read “How to Raise a Reader.” The combination of watching the film and reading the book so closely together sparked an insight: when we celebrate a chess champion, we value neurodiversity. But [pullquote]when we over-focus on the minority of student readers who need unusually little instruction to understand patterns of written English, we ignore and punish neurodiversity.[/pullquote]

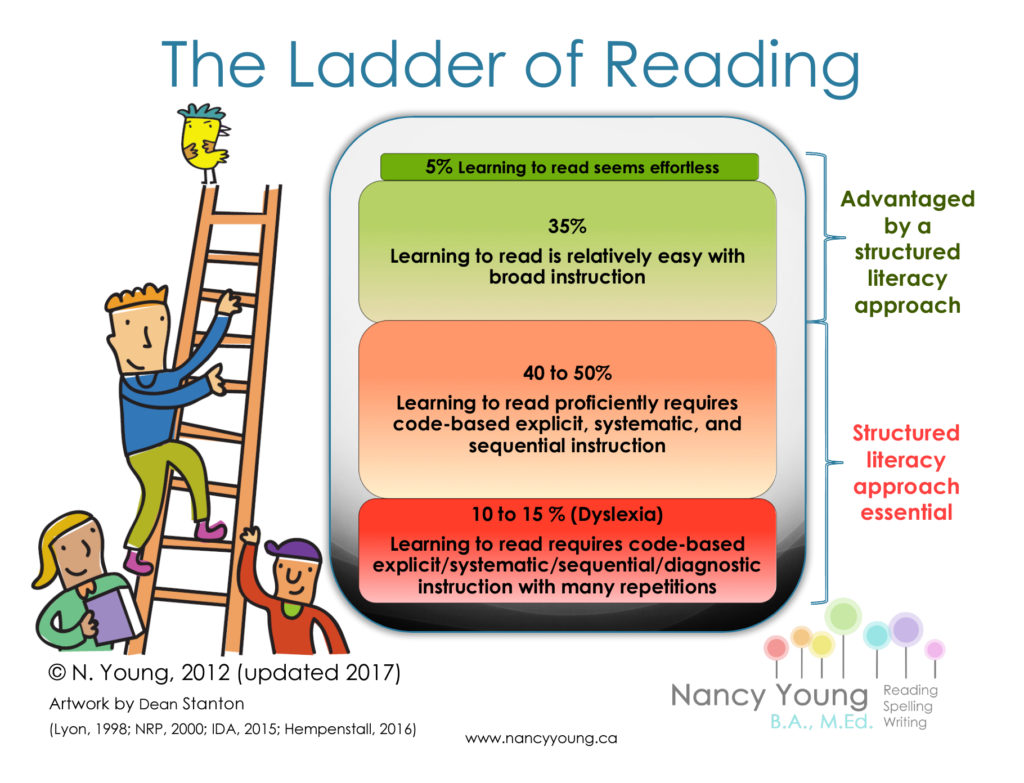

To understand neurodiversity in reading, you might watch Kelly Sandman Hurley’s TED Talk and you might look at Nancy Young’s Ladder of Reading. As Hurley’s TED Talk mentions, not all kids will learn to read solely from the instruction available to them in school. The pandemic has brought this truth home to parents. With parents co-teaching their children at home, they can see when their children lack reading skills and when teachers aren’t meeting their needs. When schools closed last spring, my phone began ringing and my email box filled up with appeals for help. And again, this fall, just as the first quarter of school was ending in New York City, I received three calls for help from families with struggling readers.

If your child were one of the 60% of children who struggle with reading to some degree, might you turn for help to a book like “How to Raise a Reader”? You might. You might even double down on some of their advice. Unfortunately, if your struggling reader is like mine was, your child still wouldn’t learn to read.

“How to Raise a Reader” begins to mislead parents from the title of Part One, “Born to Read.” In fact, nobody was born to read. Though we don’t know exactly when humans developed spoken language, we know it happened much earlier than the development of written language. Mass printing came along even more recently. The Chinese invented movable type around 1000 C.E., and Gutenberg’s press, which made mass-produced books possible, only arrived around 1450.

I doubt the authors of “How to Raise a Reader” meant to suggest that reading is a natural process. But [pullquote]it is important to stress that reading doesn’t come to many children naturally[/pullquote], the way speech usually does. And reading did not magically become natural when it became easier to mass-produce books and newspapers.

Authors Pamela Paul and Maria Russo do offer a lot of great advice about reading to babies and toddlers. It is important to help your child develop an appreciation of books, vocabulary, syntax and knowledge. But you need much more to develop a love of reading, and this book fails to address some key steps in the process.

Instead, Paul and Russo jump from a section on emerging readers to a section on independent readers without addressing reading instruction at all. Granted, the book is not titled "How to Teach a Child to Read," but without giving parents some fair warning about what to look out for in school, it reinforces the lack of clarity most parents face in understanding the gap between what works to help children learn to read and the actual instructional practices most prevalent in schools.

Most parents are not aware that most teaching colleges do not effectively prepare K-3 teachers to teach reading. In most states, teachers in grades K-3 are not required to prove their ability to teach reading to be licensed. [pullquote position="right"]Most parents expect that when they drop their kid off at school, that kid will be taught to read. Unfortunately, that is not the case often enough[/pullquote] that even a book about “raising” rather than “teaching” a reader would better serve parents by taking on this topic.

Worse, Paul and Russo get it wrong when they suggest that the way dyslexic students learn to read is different from how other students do it. In fact, the majority of students benefit from being taught to read in the same fashion that works best for dyslexic students: using explicit, sequenced reading instruction that takes a diagnostic approach and is delivered with fidelity to an evidence-based program. This is what works for 60% of students. A quarter of those 60% are dyslexic and need significantly more practice in each part of the sequence than others.

If every student were offered this kind of explicit instruction in reading, all of them would become even stronger readers. Sadly, such instruction is not available in most public schools; the results are low literacy rates throughout the nation and a strong tutoring industry for those who can afford it.

Perhaps the next edition of this book will include “How to Advocate for Good Reading Instruction at School” and include the hallmarks of good instruction. Since dyslexia affects almost 20% of the population, perhaps a few of the warning signs of struggling readers could be included. And then perhaps, we can improve upon the 34% of eighth graders that read at grade level and we can begin to dismantle the dyslexia-to-prison pipeline. We might even create more love for books. And maybe we will all even pick up a book as often as we binge-watch a show on Netflix.

Debbie Meyer is a founding member of the Dyslexia (Plus) in Public Schools Task Force, a small group of community leaders working to help students with dyslexia and related language-based disabilities thrive in their neighborhood schools. She also serves as a board member of both the Dyslexia Alliance for Black Children and Harlem Women Strong, and is a member of the Arise Coalition Literacy Committee. Most recently, she was appointed as a contributor to NYC Mayor Eric Adams Transition Team. In 2018, she was named as an A’leila Bundles Community Scholar at Columbia University to look at the intersection of dyslexia and mass incarceration and the role of universities in changing the trajectory of struggling readers. Debbie’s lengthy professional career is in nonprofit management and fundraising. She lives in Central Harlem with her [dyslexic] husband and son.

Few issues in education spark more tension and debate than standardized testing. Are they a tool for equity or a burden on students? A necessary check on school systems or a flawed measure of...

Charter schools are public schools with a purpose. Operating independently from traditional school districts, they're tuition-free, open to all students, and publicly funded—but with more flexibility...

Despite the benefits of a diverse teaching force, prospective teachers of color fall out of our leaky preparation pipeline at every stage: preparation, hiring, induction, and retention. Here’s what...

Ed Post is the flagship website platform of brightbeam, a 501(c3) network of education activists and influencers demanding a better education and a brighter future for every child.

© 2020-2025 brightbeam. All rights reserved.

Leave a Comment