Jan 24, 2024 2:53:06 PM

by Laura Waters

The fight for educational equity has never been just about schools. The real North Star for this work is providing opportunities for each child to thrive into adulthood. This means that our advocacy must go beyond the walls of the classroom and encompass what many call “the whole child.”

Another way to look at this is by targeting the essential supports necessary for the development of a healthy human being.

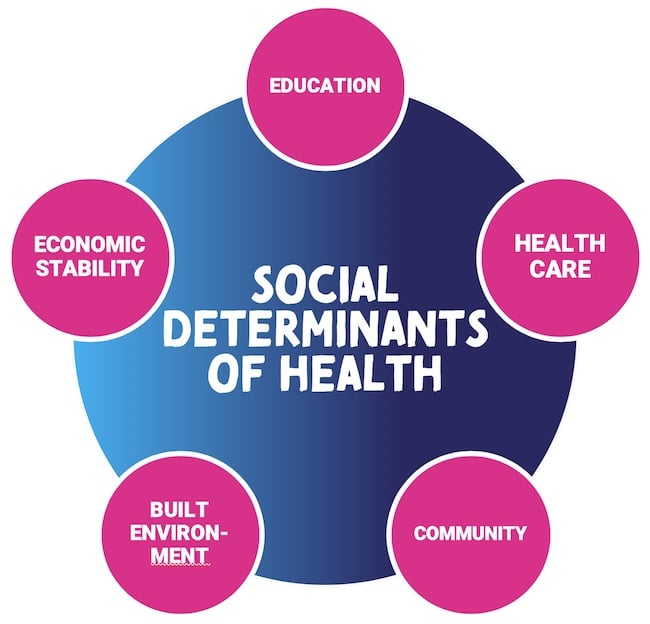

Education is just one pillar of the many social factors that contribute to this foundation. You also need access to decent health care. You need the relationships and support of a community. You need clean water and safe, habitable buildings and neighborhoods. You need economic security.

In public health work, they call these the “social determinants of health” (SDoH).

What Are “Social Determinants of Health [SDoH]” and Why Should You Care?

Each pillar of the SDoH involves much more than whether you are sick. Many factors—where you live, whether you graduate from college, where you work, how much money you make, the level of crime in your neighborhood, your access to healthcare—contribute to your state of wellness.

Too often the advocates focused on justice in each of these pillars focus narrowly on their own sector, nearly to the exclusion of the other four (guilty!).

But "the interplay of these determinants plays a critical role in outcomes for children." For example, years after the massive disruption of Hurricane Katrina, over one-third of youngsters displaced by the flooding had clinical diagnoses of mental illness.

In a post-pandemic world, we’ve all been affected by fear and isolation. Many have lost jobs, income, and, worst of all, loved ones. These traumas are especially acute for those who live in poverty (disproportionately Black or Brown) or have chronic health conditions. In other words, a vaccine specifically targeted to overcome a virus is only one factor in healing from a pandemic.

In fact, the disproportionate toll of the coronavirus on Black and Brown Americans is itself a sign of the critical role SDoH plays in the trajectories of our lives. Dr. Marcella Nunez-Smith, director of the Equity Research and Innovation Center at Yale School of Medicine, calls this “a legacy of structural discrimination that has limited access to health and wealth for people of color.”

This doesn’t spell doom. It spells the urgent need for change.

How Do SDoH Affect Children?

Sufficient access to each of the five pillars is never more critical than during childhood.

Think about it: Environmental factors—lead in the water in Flint, Michigan and Newark, New Jersey—cause brain damage in children. Crime-ravaged neighborhoods cause higher rates of drug use and mental disorders: Some doctors say a child’s ZIP code is a stronger predictor of health than his or her genetic code.

There’s a clear correlation—some would argue causation—between your parents’ income and your odds of ending up in prison. For example, Nashville, Tennessee, has a 14% rate of incarceration, the highest in the country, as well as the highest child poverty rates (42%).

But the most important SDoH for children is school: Says one expert, “Education is the single most important modifiable social determinant of health. Income and education are the two big ones that correlate most strongly with life expectancy and most health status measures.” The difference is stark: People who never finished high school, according to a 2010 report, had a six-year shorter life expectancy than those with a high school diploma.

The role of education as an SDoH ripples outwards, affecting many aspects of life—and death. According to the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the mortality rate for infants born to mothers who didn’t finish high school is twice as high as for mothers who did. Children whose parents didn’t finish high school are far less likely to finish high school themselves. Even one year of college leads to a 11% increase in income and four years leads to a reduced risk of heart disease, diabetes and obesity. Children born to parents who didn’t finish high school have less than a 6% chance of getting a four-year college degree. Those born to parents who have a four-year college degree have a 49.5% chance of getting that degree themselves. Those lucky kids with parents who are college graduates are disproportionately Asian (50%) and White (30%), while only 17% are Black and 12.6% are Hispanic.

And it’s not about just attending school. School quality is a major SDoH because low-achieving schools have negative effects not only on a child’s learning but also his or her attitudes, behaviors and wellness. Children who are unmotivated in school are more likely to be afflicted by asthma, ADHD, poor vision and food insecurity. We all know that some schools prepare students for college and careers more effectively than others, which then affects those students’ lives and the lives of their children. “Studies have shown,” reports the National Institutes of Health, “that children who enroll in poor-quality schools with fewer health resources, more violence, and a distressed school climate are more likely to set forth on a path toward worsened physical and mental health.”

It’s a vicious cycle.

What Can We Do to Create Positive Determinants for Ourselves and Our Children?

We’re in the midst of the worst pandemic since the 1918 Spanish flu, the worst racial unrest since the 1967 civil rights riots and the highest unemployment rate since the Great Depression. It’s hard to think of a time when the social determinants of health loomed larger or when the spotlight was brighter on structural inequities baked solidly into our culture.

We can start with urging local, state, and federal officials, when they go through the necessary exercise of cutting budgets, to go easy on schools, nonprofits, advocacy groups and social service organizations that serve those with the greatest needs.

And, because the most critical SDoH is school quality, we must find ways to expand our high-performing schools and expand parents’ abilities, regardless of ZIP code, to enroll their children in buildings that can break the cycle of poor educational outcomes begetting another generation of poor educational outcomes.

Editor's note: this article was originally posted June 5, 2020 and has been updated.

Laura Waters is the founder and managing editor of New Jersey Education Report, formerly a senior writer/editor with brightbeam. Laura writes about New Jersey and New York education policy and politics. As the daughter of New York City educators and parent of a son with special needs, she writes frequently about the need to listen to families and ensure access to good public school options for all. She is based in New Jersey, where she and her husband have raised four children. She recently finished serving 12 years on her local school board in Lawrence, New Jersey, where she was president for nine of those years. Early in her career, she taught writing to low-income students of color at SUNY Binghamton through an Educational Opportunity Program.

Few issues in education spark more tension and debate than standardized testing. Are they a tool for equity or a burden on students? A necessary check on school systems or a flawed measure of...

Charter schools are public schools with a purpose. Operating independently from traditional school districts, they're tuition-free, open to all students, and publicly funded—but with more flexibility...

Despite the benefits of a diverse teaching force, prospective teachers of color fall out of our leaky preparation pipeline at every stage: preparation, hiring, induction, and retention. Here’s what...

Ed Post is the flagship website platform of brightbeam, a 501(c3) network of education activists and influencers demanding a better education and a brighter future for every child.

© 2020-2025 brightbeam. All rights reserved.

Leave a Comment