Aug 6, 2019 12:00:00 AM

As a high school English teacher, I had the privilege of teaching Toni Morrison’s “Beloved,” a novel I’ve read and taught time and again, and one that never fails to overwhelm with awe, silence and turmoil.

Towards the middle of the novel, Sethe, a runaway slave, is found by her former master. Rather than see her children be taken into slavery, Sethe kills one of her children, a daughter.

I choose to read the scene out loud to students, the classroom resonating with images of baby’s blood, fear, horror and despair. We argue over Sethe’s love for her children, a love that gave her the strength, if indeed it was strength, to draw the teeth of a saw along the throat of her babe.

I’ve done this for years. Dozens of students have visited school after they’ve graduated and have recalled this specific read-aloud as one of the most powerful moments in their high school education.

And time and again, my students, almost all of whom are Black, say things like, “I knew about slavery, but I didn’t know about slavery.” And their eyes water.

This specific read-aloud moment came to mind as I learned of Toni Morrison’s passing. She was a national treasure and a literary giant; [pullquote position="right"]she was our greatest teacher regarding how we might teach the hardest lessons of our tragic history.[/pullquote]

According to “Teaching Hard History: American Slavery,” a report by the Southern Poverty Law Center, nearly 90% of teachers say “teaching and learning about slavery is essential to understanding American history.” But it also notes that many teachers feel uncomfortable teaching slavery and don’t find their existing curricular materials or their state's standards to be much help. Specifically, the lessons in current textbooks and standards present “focus on politics and economics, which means focusing on the actions and experiences of White people.”

I, thankfully, didn’t teach “Beloved” during my first year of teaching. That would have been a disaster. Teaching this history, particularly as a White educator, requires deep introspection, reckoning and the humility to ask for support. I am blessed to be surrounded by colleagues of color who were, and are, patient with my ignorance and naïveté and take the time to educate me, something that they surely do not have to do.

I had to think about how to present “Beloved,” its story and its history in a meaningful way that not only honored the power of Morrison’s work, but also honored the very real people who not only experienced the dehumanization of slavery, but sought myriad ways to demonstrate and protect their humanity. Further, I had to teach the story in a way that also acknowledged the generations who came after, including today’s, who continue to feel the effects of 400 years of chattel slavery right here in the “Land of the Free.”

I supplement Morrison’s words and her characters with sepia-toned images of slavery in the United States. We read of Sethe’s chokecherry tree of scars along her back, and then sit in silence facing the undeniable realness of a slave named Gordon. We read of Paul D, a friend of Sethe’s, being punished by his slave master by being forced to wear a bit in his mouth, and then face the shocking image of spiked collars that were used to punish real people right here in America.

The most important stories in history can be diluted by statistics and impersonal, omniscient narratives spoken from a birds-eye view from up on high. To teach this history, to tell this story, I had to bring it back down to earth and focus on a single truth—these were people. This happened here. This is our past, and it is inextricably connected to our present. This is us.

When I read the notification on my phone that Toni Morrison had died, I nearly drove off the road. It was immediately clear that [pullquote]we had lost a titan—a defining American voice; one that had the courage to sing of America’s blood-stained hands with a passion, beauty and an unflinching realism unparalleled[/pullquote] in American literature.

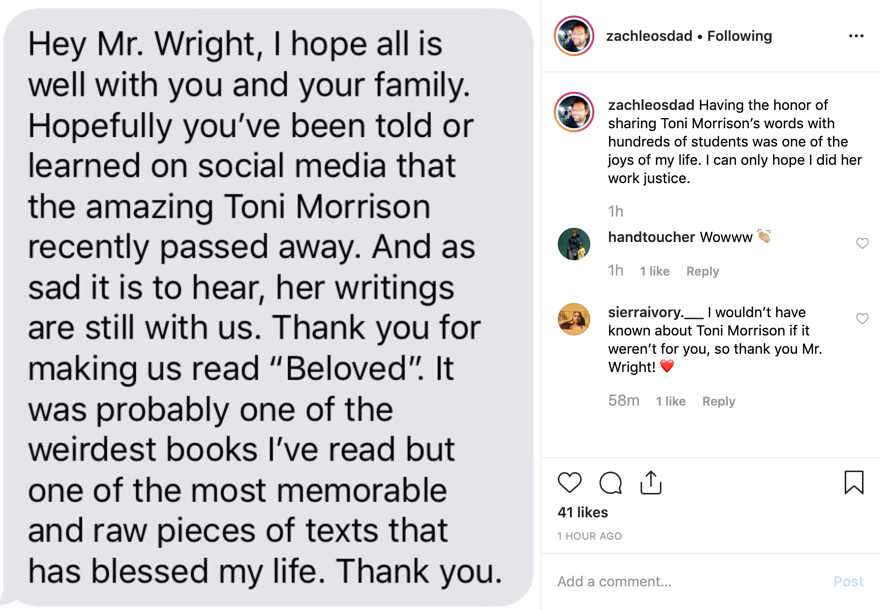

Less than an hour later, the texts rolled in; texts from former students recalling memories of reading “Beloved” and “The Bluest Eye” and “Recitatif” in my classroom; expressions of gratitude for exposing them to such challenging and necessary works.

Morrison’s works serve to awaken our national amnesia, forcing us to re-remember scenes of intense violence, brutality, horror and, yes, love. It is up to us as educators to pass these words to our students, to equip ourselves with the skills to do her words justice. For, as Morrison told us, cryptically as ever, these are not the stories to pass on.

Zachary Wright is an assistant professor of practice at Relay Graduate School of Education, serving Philadelphia and Camden, and a communications activist at Education Post. Prior, he was the twelfth-grade world literature and Advanced Placement literature teacher at Mastery Charter School's Shoemaker Campus, where he taught students for eight years—including the school's first eight graduating classes. Wright was a national finalist for the 2018 U.S. Department of Education's School Ambassador Fellowship, and he was named Philadelphia's Outstanding Teacher of the Year in 2013. During his more than 10 years in Philadelphia classrooms, Wright created a relationship between Philadelphia's Mastery Schools and the University of Vermont that led to the granting of near-full-ride college scholarships for underrepresented students. And he participated in the fight for equitable education funding by testifying before Philadelphia's Board of Education and in the Pennsylvania State Capitol rotunda. Wright has been recruited by Facebook and Edutopia to speak on digital education. In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, he organized demonstrations to close the digital divide. His writing has been published by The Philadelphia Inquirer, The Philadelphia Citizen, Chalkbeat, Education Leadership, and numerous education blogs. Wright lives in Collingswood, New Jersey, with his wife and two sons. Read more about Wright's work and pick up a copy of his new book, " Dismantling A Broken System; Actions to Close the Equity, Justice, and Opportunity Gaps in American Education"—now available for pre-order!

Few issues in education spark more tension and debate than standardized testing. Are they a tool for equity or a burden on students? A necessary check on school systems or a flawed measure of...

Charter schools are public schools with a purpose. Operating independently from traditional school districts, they're tuition-free, open to all students, and publicly funded—but with more flexibility...

Despite the benefits of a diverse teaching force, prospective teachers of color fall out of our leaky preparation pipeline at every stage: preparation, hiring, induction, and retention. Here’s what...

Ed Post is the flagship website platform of brightbeam, a 501(c3) network of education activists and influencers demanding a better education and a brighter future for every child.

© 2020-2025 brightbeam. All rights reserved.

Leave a Comment