Feb 28, 2023 2:03:52 PM

by Lami Zhang

Black History is under attack–due both to fallout from the recent culture-war frenzy and to entrenched problems with schools taking a limited view of the subject.

Despite these obstacles, innovative teachers within and outside traditional public schools are setting the standard for a more expansive and empowering view of Black history than many students typically receive.

In doing so, they are fulfilling Carter G. Woodson’s original vision when he created Black History Week: to make space in schools for serious study of the greatness of Black people, both in Africa and in the African diaspora, including the United States.

How are they doing it? By starting with a foundation in Africa and weaving Black history across the entire curriculum. These teachers also are keenly aware of the potential chilling effect of recent legislation and offer tips on how their fellow educators can protect themselves from possible challenges.

Ed Post contributor ShaRhonda Knott-Dawson co-founded the racial equity organization BRONDIHOUSE, which offers workshops and classes on Black history to public schools as well as other groups. The curriculum emphasizes study of African civilizations, both as far back as 2500 BCE with the Nile River Valley civilizations and also the more recent West African empires between 200 CE and 1500 CE.

She said current Black history education in U.S. schools over focuses on recent examples of outstanding Black individuals, like Martin Luther King Jr. A more accurate and encompassing approach to Black history explores Black communities and their contributions to the world prior to European colonialism.

“There was this idea that Black and Brown people came from nothing, that they weren’t smart and that people were savages,” she said. “It puts this idea that science and math was created and is owned by these white men and white cultures, which is not true.”

Through BRONDIHOUSE workshops, Knott-Dawson aims to educate Black and Brown students on the greatness of their ancestors and their contributions to world civilizations, from the great pyramids of ancient Egypt to the universities of Timbuktu. This is a history that isn’t centered around deficits or whiteness.

“There was an intentional erasure of our history in order to justify what happened to us,” she said. “This information is missing, because that’s the only way that you could justify slavery.”

Although this history is missing in many traditional classrooms, teachers Abigail Henry and Anika Prather agree with Knott-Dawson that schoolchildren need to know Black history did not begin with enslavement.

Henry, who has taught Black history at Mastery Charter School–Shoemaker Campus in West Philadelphia for the last 11 years, spends three weeks on the study of Africa and some of its civilizations, including African geography, ancient Mali and the kingdom of Kongo, and key socio-religious topics in the region.

Traditional interpretations of European and Mediterranean history often minimize the role of people and ideas from the African continent, even though North Africa is part of the Mediterranean and was part of the Roman Empire.

Prather, co-author of The Black Intellectual Tradition and founder of an online, private, Christian school, The Living Water School, works hard to show students the connections between Black history and classical Western culture. She has had to do her own research to highlight the connections.

“There’s this other story around classical learning that needs to be told with Black history. To not know this educational philosophy, you’re actually missing a major part of Black history and our struggle for liberation and equality,” Prather said.

For example, she introduces students to the Roman playwright Terence, who was born in what is now Tunisia. Terence’s plays, highly regarded throughout the Roman Empire, became the source of the modern comedy of manners.

The Black experience over centuries cannot only be discussed in history classes, but must also be included in science, math, literature and the arts. Across all subjects, schools and teachers need to find a balance between teaching the truth about structural injustices and exploring historical narratives in ways that build young people’s identity and agency.

According to Prather, an inclusive academic curriculum is about asking a simple question. “You can take whatever time period, whatever subject you’re teaching, and ask yourself the question: ‘Who else was there?’ and you will find a person of color.”

Prather makes this come alive for her students across time periods and academic disciplines, from Phillis Wheatley’s Latin-filled poetry to the influence of Plato on Huey Newton’s leadership of the Black Panthers. She encourages her students to analyze primary sources.

“A lot of times, we are using textbooks that are giving someone’s opinion on history,” Prather said. “But when you read it from the person’s mouth- where they stood and what they believed- and you present those primary sources to children, they can then make fair assessments of what’s really going on here.”

Experts say traditional American history curriculums present a narrow picture of the African American experience. The Johns Hopkins Institute for Education Policy (IEP) found that history curriculums in U.S. schools often lean into the negative aspects of the Black experience without attending as closely to Black achievements and accomplishments.

Typical lessons also overlook key historical milestones necessary for the full picture of Black history. Lessons tend to cover enslavement in the U.S and the civil rights movement, but often ignore the Harlem Renaissance and the Great Migration.

Teacher knowledge of Black history varies widely, which can lead to “strikingly superficial” classroom treatments of the topic, said Ashley Berner, the director of IEP at John Hopkins. Most education colleges in the U.S. do not require teachers to take critical race theory or ethnic studies classes, which leads to a lack of preparation regarding teaching essential parts of history.

“It’s very easy for a curriculum to either gloss over painful struggles in our country’s history or, conversely, to focus so much on structural inequality that kids don’t have a sense of their own agency,” Berner said.

Educators and parents worry this narrow focus has prevented generations of students from developing a healthy concept of Blackness.

To fill the gap, organizations from the Zinn Education Project to the Langston League have developed programs and resources that supplement teachers’ often-skimpy education in Black history. For example, the Langston League, a curriculum design firm, designs culturally relevant lessons that combine Black history with pop culture. The firm also offers Decolonized, a free YouTube channel offering a fresh take on Black history, with a special emphasis on place-based learning.

As part of its Teaching for Black Lives Campaign, the Zinn Education Project provides teachers with free lessons in social history, including Black history. The nonprofit has published a book, Teaching for Black Lives, and supports teacher study groups putting it to work across the nation. As part of its Teach the Black Freedom Struggle series, the nonprofit also holds monthly online classes for teachers and students from leading historians.

Building a quality, comprehensive Black History curriculum is just the first step. “In order to teach some of those more delicate and difficult parts of American history, you have to build a classroom community on a foundation of trust and mutual respect,” said Jesse Hagopian, a high school history teacher and lead organizer with the Zinn Education Project.

At the start of every school year, Henry leads an open and vulnerable conversation with her students regarding their experiences with racism.

“On the first day of school, I tell kids about the first time I was ever called the N word. The first homework assignment is for them to write me a letter telling me about themselves and whether or not they’ve experienced racism,” she said.

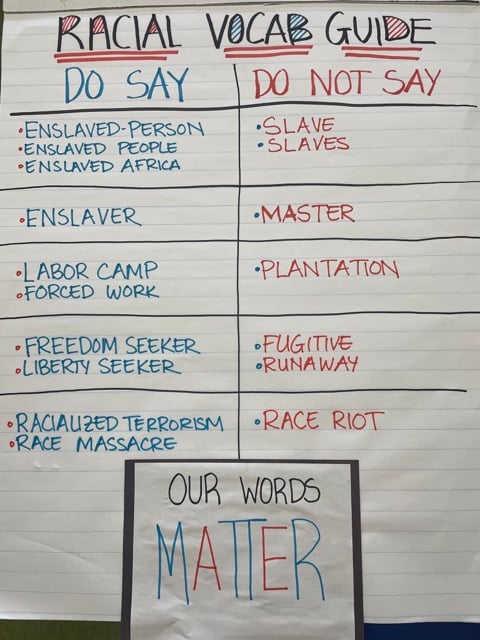

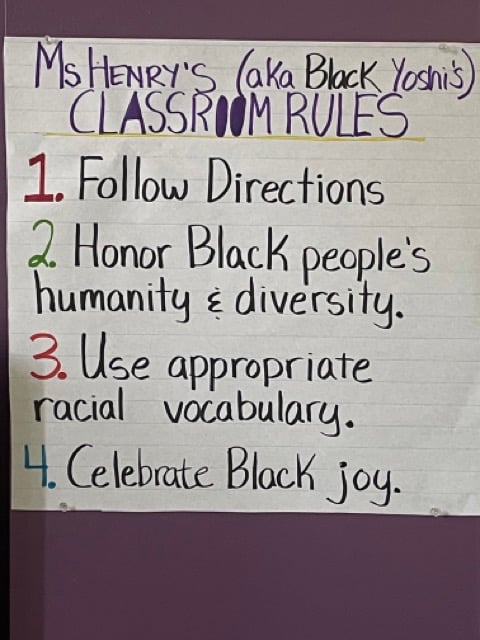

She then spends the next few days going over racial vocabulary, which sets the tone for mutual respect and transparency in her classroom.

Posters from Henry's classroom. (photos from Abigail Henry)

Beyond setting an appropriate tone for her lessons, Henry also creates space for students to process their emotions.

“I always say to the kids, my number one goal is not to traumatize you. I tell kids when our lesson is heavy, like when I did the Dred Scott decision, for example, you’re about to read the judge’s decision. It should make you angry,” she said.

She also knows her students well enough to know their particular circumstances and issues. She estimates about 10% of her students have incarcerated family members. ”So, when I’m giving a lesson on convict leasing during Reconstruction, I have to be very careful about how I teach it.”

On a macro level, there needs to be clear policies that are protective of teachers while they teach these frameworks, Hopkins’ Berner said.

“Strong leadership at the school district level is needed to say to parents and teachers, ‘we are going to talk about tough stuff and it’s going to be uncomfortable,’ but this is part of the democratic process.”

In the past few months, teaching Black history has been embroiled in political controversy, following Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis’ decision to ban AP African American Studies in his state and the ensuing revised framework by the College Board. Educators across the country are worried about the effects this culture war is having on how they can teach Black history to students.

In light of current curriculum battles around African American studies, Henry suggests framing a lesson around the learning standards it teaches rather than focusing on its historical content.

She also suggests reaching out to families in the community and sharing the curriculum students are learning in the classroom.

“Reach out, especially, to families of color; I am concerned that their voices are being lost in these curriculum battles,” Henry wrote in a piece for Chalkbeat Philadelphia.

It’s also important to make sure Black history doesn’t disappear from the classroom after February ends.

Hagopian insists schools must include Black lives and stories in all aspects of the curriculum, all year long.

“There are so many incredible contributions that Black people have made to this land in art, music, culture, science, architecture, engineering and democracy,” Hagopian says. “Those stories have to be told alongside the stories of violence to Black bodies in order to gain a complete picture.”

Lami Zhang is an editorial intern at Brightbeam. She is currently a fourth year undergraduate student at Northwestern University studying Journalism and Political Science.

Few issues in education spark more tension and debate than standardized testing. Are they a tool for equity or a burden on students? A necessary check on school systems or a flawed measure of...

Charter schools are public schools with a purpose. Operating independently from traditional school districts, they're tuition-free, open to all students, and publicly funded—but with more flexibility...

Despite the benefits of a diverse teaching force, prospective teachers of color fall out of our leaky preparation pipeline at every stage: preparation, hiring, induction, and retention. Here’s what...

Ed Post is the flagship website platform of brightbeam, a 501(c3) network of education activists and influencers demanding a better education and a brighter future for every child.

© 2020-2025 brightbeam. All rights reserved.

Leave a Comment