May 17, 2022 2:49:45 PM

by Jay Wamsted

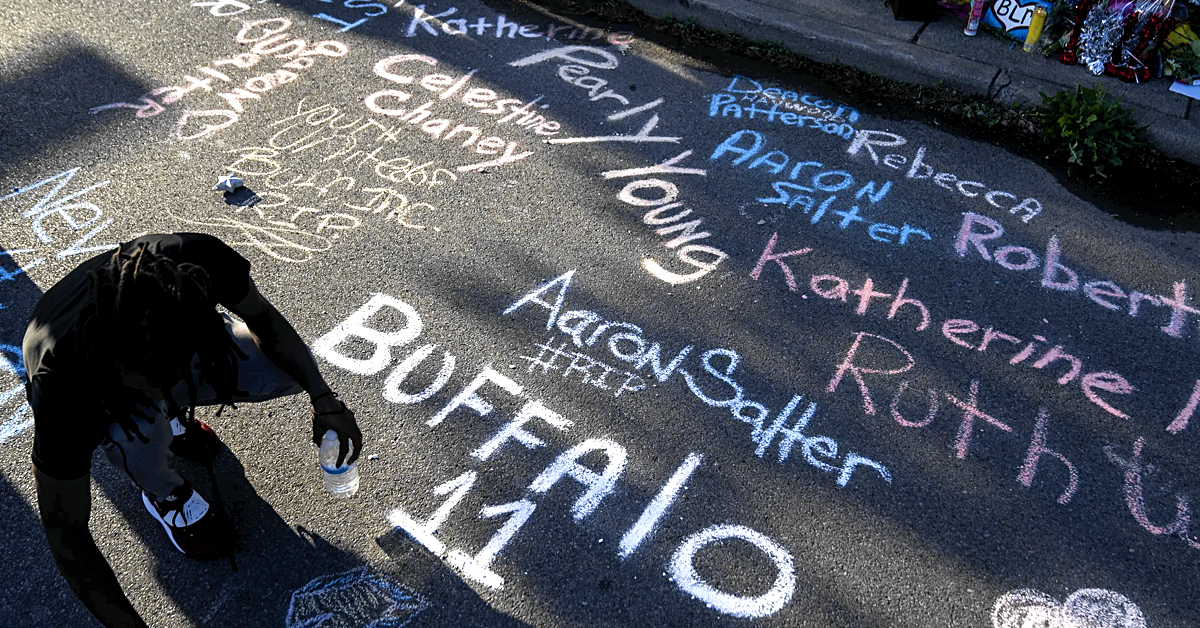

It didn’t take long for them to ask. Just a little bit of downtime and a student approached. “Mr. Wamsted, did you hear about the shooting in Buffalo?”

All around the country, teachers went to school faced with a terrible choice.

Math teachers, language teachers, science teachers, and especially social studies teachers—we all approached our buildings thinking about Buffalo. We all wondered what we were going to say to our students.

Some teachers had it better than others. They work in schools that affirm conversations about racism and white supremacy, they are free to act as if the well-being of their students is based on more than proper use of the Pythagorean Theorem or a detailed reading of the Periodic Table. They are free to attend to the emotional health of the young humans in their charge.

Many of us, however, experience no such grace. We work in states that have passed laws outlawing conversations about “divisive concepts” like race. Never mind that the shooting this weekend was prompted by a dangerous conspiracy theory centered around race—replacement theory. Never mind that the shooter was explicitly motivated by the age-old foundations of white supremacy.

According to many states, including mine, talking about the motivations of the shooter would be “divisive.”

I have no doubt that some, though certainly not all, of these “divisive concepts” laws are motivated in part by something like good intentions. I am sure there are well-meaning legislators out there who are just trying to protect children from conversations perceived to be beyond their maturity level. Of course, these legislators aren’t thinking about the children who are exposed to hatred and racism on a regular basis—they are, quite frankly, only thinking about the abstract white child. They are trying to protect a racial innocence that they perceive to be aspirational.

Well-meaning, maybe. But let us heed the words of Ta-Nehisi Coates:

It matters not how well-meaning these laws might be. Their effect is stark: they handcuff necessary conversation by sowing doubt in the minds of educators. They perpetuate “the Dream” of white superiority by refusing to allow conversation about its obverse: anti-Black hatred.

Some teachers went to school today in fear. We worried about whether to talk about Buffalo and, if we so chose, we worried about how to do it. If we decided against the conversation—fearful of repercussions from administration, parents, or the district—we worried about what we would say if a student brought up the shooting.

A hall pass through history. That’s what these “divisive concepts” laws feel like—a slip of paper letting another generation of white people off the hook for having to deal with our legacy of racism and violence.

It didn’t take long for them to ask.

What is a teacher supposed to do in such a moment? Do we accept the hall pass and keep on moving through our lesson plans? Or do we stop and let the moment lead us to something arguably more important? Do we pretend that racism had nothing to do with Buffalo? Or do we push back against these hall-pass laws?

Another quote comes to mind. You might know the words best from the movie "The Usual Suspects," uttered by Keyser Söze, but they were first written by Charles Baudelaire: “The loveliest trick of the Devil is to persuade you that he does not exist.”

“Divisive concepts” laws want us to believe that racism is no longer a factor in American society, that the devil so many know so well is merely a phantom. I know I’m not alone, however, in finding such a sentiment hollow.

Like the well-meaning legislator, I want to live in a world where we don’t need to have terrible conversations about hatred and racism. In the meantime, though, as we do the hard work of moving toward such a thing let us roll back these insidious laws and teach the truth. Let's have difficult conversations with kids who are mature enough to ask important questions.

Some teachers were put in an unconscionable position this week. Let’s work to make sure that never happens again.

Jay Wamsted has taught math at Benjamin E. Mays High School in southwest Atlanta for fourteen years. His writing has been featured in various journals and magazines, including "Harvard Educational Review," "Mathematics Teacher" and "Sojourners." He can be found online at "The Southeast Review," "Under the Sun" and the "TEDx" YouTube channel, where you can watch his 2017 talk “Eating the Elephant: Ending Racism & the Magic of Trust.” He and his wife have four young children, and he rides his bicycle to and from work just about every day. You can contact him on Twitter @JayWamsted or by email, wamsted@gmail.com.

Few issues in education spark more tension and debate than standardized testing. Are they a tool for equity or a burden on students? A necessary check on school systems or a flawed measure of...

Charter schools are public schools with a purpose. Operating independently from traditional school districts, they're tuition-free, open to all students, and publicly funded—but with more flexibility...

Despite the benefits of a diverse teaching force, prospective teachers of color fall out of our leaky preparation pipeline at every stage: preparation, hiring, induction, and retention. Here’s what...

Ed Post is the flagship website platform of brightbeam, a 501(c3) network of education activists and influencers demanding a better education and a brighter future for every child.

© 2020-2025 brightbeam. All rights reserved.

Leave a Comment