Apr 19, 2022 5:47:36 PM

When I was a kid, my mother would tell me, “One monkey don’t stop no show!”

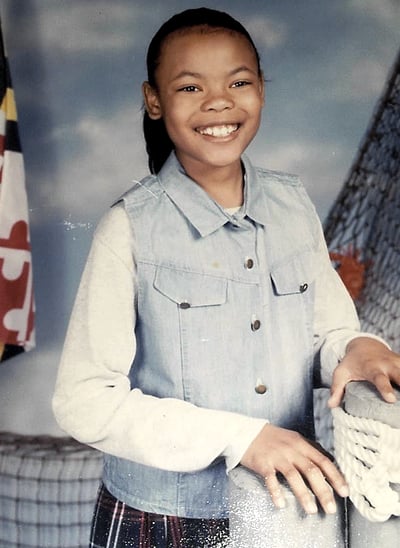

I was in kindergarten—snaggle-toothed, bright-eyed, and brown-skinned, with a head full of knocker-balls that clacked like high heels when I walked. Her words cut through the sound of my sobbing to stop the tears in my throat.

“Monkeys?” I scrunched my face.

“The show goes on, Ash. This world is gonna try you. But don’t let nothing or nobody make you feel less than or that you don’t belong.”

Like an ointment, my mother spread these words across my first emotional wound. A few hours before, a girl from my class with freckles and pigtails said that she would not play with me. No more hopscotch or jump rope on the blacktop at recess. No more criss-cross applesauce during read-aloud. No more sharing treats during lunch.

Her rejection hurt, of course, but the real rub was that it didn’t make any sense. What did skin have to do with anything? I realized then that I was one of the very few brown-skinned children in my school. I wondered if everyone felt the same way as my former friend. I was six years old, and while it was the 90s, in a relatively progressive state, this event was a thread in a pattern that would be woven throughout the fabric of my youth. I possessed neither the language nor the tools to help me navigate the complicated emotional landscape these experiences elicited within me.

Toni Morrison would tell her students at Princeton, “Don’t write what you know.” When I was 16, I began to write about what I could only imagine. At night, hours after my parents and siblings had drifted off into the embrace of sleep, stories about Black children born with magic in their bones flowed out of my fingers across the keyboard. In one story, a girl named Maya sprouted wings to soar above the cruelty of bullies. I wanted to be like Maya and all of the children in these stories who were granted the gift of transcendence.

“This is really good, Ash!” My mom waved the printed story, clenched in her hand, so hard that a breeze blew across my face.

“You think so?” My eyes remained glued to my sneakers.

“Sure do. I’ll let my Department Chair read it. You should be published, girl!” My mother worked as an administrative assistant in an academic department of a university in Baltimore, Maryland.

“I don’t know, Ma.”

“But this is really good. I’ll take it in. You gotta learn to advocate for yourself, Ash.” She tossed her neck back in laughter, still waving my story like a flag on the Fourth of July.

Three weeks later, we heard back from the Department Chair. My mother said he dropped my story on her desk like something too hot to hold. He said without a stumble that it was plagiarized. His college students couldn’t write as well, and he didn’t for a moment think that I could either. He couldn’t help—except to remind my mother about the ethical and legal implications of piracy.

A cobra of anger uncoiled in my gut.

The pain of chronic racism and marginalization stewed inside me. By the time I got to college, I was clinically depressed and hardened with hate. At 19, I would go on to win my first literary award and half a dozen publications would follow. But even with the recognition, there were days when I wanted to disappear.

By my mid-20s, I let nothing give away the raging hurricane of untamed emotions storming inside me. I held it all in.

But then I stumbled on a concept called “emotional intelligence.” Emotional intelligence is defined as the ability to “recognize, understand, and manage our own emotions,” and the ability to “recognize, understand, and influence the emotions of others.” The skillset also involves effective communication, self-regulation, positive stress relief and overcoming challenges.

These resources and techniques, which include mindfulness, were such a relief to me. It was like the first gasp of air after holding in your breath for so long.

Emotional intelligence granted me my childhood wish—the power to walk through human challenges and not be marred by them. It taught me how to sit with myself in kindness and compassion. It taught me forgiveness. It taught me to evaluate my emotional patterns without reactivity. I noticed myself changing without even trying. Practicing emotional intelligence softened my sarcasm, made me more empathic and tamed my quiet rage. It helped me to settle into myself. It fortified my desire to live and seeded my determination to do it with some gumption, some grace, some joy, some humor and some passion.

The benefits of emotional wellness are well-documented. In children, higher emotional intelligence translates to better engagement in school, better behavioral regulation and higher academic achievement. Adults with emotional wellness have stronger relationships, improved physical and mental health, and higher lifelong earnings.

This question, coupled with my background in education, led me to create an emotional health software for youth called Clymb. Backed by the American Heart Association, Clymb uses evidence-based emotional wellness assessments and resources to help young people learn how to evaluate and understand emotions, reduce toxic stress and increase resilience.

Emotional wellness changed my life. And it can save and transform the lives of countless others, especially in a time with the COVID-19 pandemic, economic hardship, hunger, war abroad and war at home with states banning our true history and jeopardizing the lives of trans students.

We must prioritize emotional health for our young people. Everyone deserves access to these life-changing tools, both those in pain and those who cause it. A lack of emotional intelligence is the basis for most social breakdowns. It’s what drives and perpetuates injustice. It’s the reason the Department Chair and parents of my childhood friend could look at me and still not see me.

In order to change systems, we have to improve the emotional competency of the people who create and maintain them. Policymakers, elected officials, parents and families, educators, neighbors, and friends should join me in calling for a movement that makes emotional health front and center.

Everyone has a story. We all grew up differently. But all of us, whatever our differences, have experienced unkindness, pain, confusion, doubt and fear. Emotional wellness can help us process, heal, and push forward through the human challenges we all walk through. With it, we learn, as my mother said: “One monkey don't stop no show.”

Ashley Williams is an emotional wellness advocate and founder of Clymb.

Few issues in education spark more tension and debate than standardized testing. Are they a tool for equity or a burden on students? A necessary check on school systems or a flawed measure of...

Charter schools are public schools with a purpose. Operating independently from traditional school districts, they're tuition-free, open to all students, and publicly funded—but with more flexibility...

Despite the benefits of a diverse teaching force, prospective teachers of color fall out of our leaky preparation pipeline at every stage: preparation, hiring, induction, and retention. Here’s what...

Ed Post is the flagship website platform of brightbeam, a 501(c3) network of education activists and influencers demanding a better education and a brighter future for every child.

© 2020-2025 brightbeam. All rights reserved.

Leave a Comment